Terry L. Meyers

With the tenement building that housed Williamsburg’s Bray School well on its way to restoration by the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, people may want to know more about the education offered at the school. We know a lot about that since the correspondence between the school’s sponsors in England and its local overseers was published in John C. Van Horne’s Religious Philanthropy and Colonial Slavery in 1985.

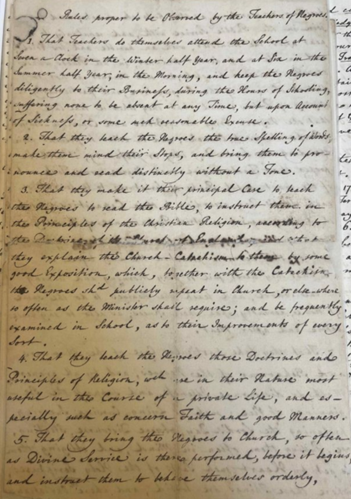

The education was almost wholly religious. Focused on “the principles of the Christian Religion as professed by the Church of England,” the concern was with “the Piety & spiritual Advantage of the children.” The white schoolmistress, Mrs. Ann Wager (who had taught the Burwell children at Carter’s Grove) was to “teach them those Doctrines & Principles of Religion, which are in their Nature most useful in the Course of private Life, especially such as concern Faith & good manners.”

But the education was also indoctrination—Blacks were taught subservience, that they were to abide by God’s divinely ordained social and racial hierarchy. Robert Carter Nicholas, Treasurer of the Royal Colony, became the principal overseer of the school and summarized what many locals thought: that it was “dangerous & impolitick to enlarge the Understandings of the Negroes, as they would probably by this Means become more impatient of their Slavery & at some future Day be more likely to rebel.”

But, Nicholas assured the Associates, their plans were “by no Means calculated to instruct the Slaves in dangerous Principles [i.e., freedom], but on the contrary. . .to reform their Manners; & by making them good Christians they would necessarily become better Servants.” The Associates were confident in asserting (with the threat of perdition) that “the tremendous Sanctions of our Religion are more likely to make honest faithful & industrious Slaves, than those who have no fear of God.” Instruction “in the Christian Religion” was deemed “the best Mean[s] to reconcile them to their state of Servitude.”

An edition of sermons to the enslaved that was sent by the Associates “for the Use of the Negroe School at Williamsburgh” is clear. The Rev. Thomas Bacon assured the enslaved that God has it all in hand: “some he hath made kings and rulers, for giving laws, and keeping the rest in order; some he hath made masters and mistresses, for taking care of their children, and others that belong to them …. Some he hath made servants and slaves, to assist and work for their masters and mistresses that provide for them.”

One of the principal skills Mrs. Wager taught was reading—necessary for the children to use in reading the Bible and religious tracts. She was to teach the children “the true Spelling of Words, make them mind their Stops [i.e. pay attention to punctuation and pacing] & endeavor to bring them to pronounce & read distinctly.”

But there were corollary lessons as well; to make them “more useful to their Owners,” the girls were taught “sewing knitting &c.” and “such other things as may be useful to their Owners.” The children were expected to “keep themselves clean & neat in their Cloaths”; Mrs. Wager was to attend to “the Manners & Behaviour of her Scholars & . . . discourage Idleness & suppress the beginnings of Vice, such as lying, cursing, swearing, profaning the Lord’s Day, obscene Discourse, stealing &c.” The children were taught “to be faithful & obedient to their Masters, to be diligent in their Business & peaceable to all men.” They were “in all Things [to] set a good Example to other Negroes.”

Whether Mrs. Wager taught writing is a contested question. Writing was a dangerous skill to teach the enslaved since they could use it to forge documents allowing them to travel freely or even to pass as free. In all the Associates’ many requests for word of the Williamsburg children’s progress and in all the reports back, writing is never mentioned. And yet almost 50 fragments of slate pencils have been found at the site of the school. The current compromise between archeologists and documentarians is that writing was “possibly” taught.

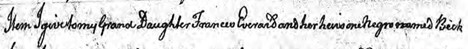

The school was the longest lasting and the most successful of the Virginia Bray schools. It opened in September 1760 and closed only in 1774, amid increasing tensions with England and with the death of Mrs. Wager. About 30 students a year, aged three to about 10, received an education at the school. Ideally the children were to attend for three years, but Franklin noted the children’s “Continuance at the School being short.” Recorded across three surviving Williamsburg lists are 94 student names, at least a few of which are duplicates. Still, this is a fraction of the total number of students likely educated at the Williamsburg Bray School. That very elusive number may be as low as 200 or closer to 400. That is a discussion for another blog.

Terry L. Meyers is Chancellor Professor of English, Emeritus, at William & Mary. This blog post is adapted from the Williamsburg Tatler (May 2023).