by Terry L. Meyers

In 2013, I suggested in an essay in the William & Mary Bill of Rights Journal, “Thinking about Slavery at the College of William and Mary,” that the Williamsburg Bray School might have inspired a possible second school for Black children also to be overseen by William & Mary. I was wrong.

But the question is still interesting because it casts some light on local racial matters not too far removed from the years the Bray School existed (1760-1774). And there is a faint echo from the Bray School.

When William Ludwell Lee (1775-1803) freed his enslaved persons, by the terms of his will, I suspect he did so at least in part under the influence of Bishop James Madison, the president of William & Mary. Madison was also the first bishop of the Episcopal Church in Virginia and cousin to the United States’ fourth president, James Madison. Bishop Madison had overseen a skepticism about slavery in the curriculum for some time, but neither he nor the College actually freed those they enslaved.

Those whom Lee had enslaved that were under eighteen were sent to be educated in a state north of the Potomac River and in accordance “with their capabilities.”

And when he specified in his will that a local “free School” be established “solely for the benefit of such persons whose indigent situation forbids their acquiring even the rudiments of an education,” I thought he must be thinking of Black children. I was encouraged in that thinking when he specified that the “American language” be taught to the pupils. I assumed Black children might be speaking a patois derived in part from their parents’ African origins, as the Atlantic slave trade was still wide open and editions of the Virginia Gazette regularly reported the arrivals of ships carrying Africans for sale.

And a final factor was Lee’s siting the school “in the centre of James City County,” as the boundaries were drawn in 1802. That location was at the center of a free Black community at what we know today as Freedom Park, located at the intersection of Longhill and Centerville Roads.

That annual payments from a gift of land were to be made to William & Mary to oversee the school, for its “use and benefit,” made sense to me since I thought (and still think) that would reflect the College’s earlier role (at least initially) in its presidents’ being overseers of an earlier school, the Bray School.

But in revisiting the question I would make several corrections, not the least of which is my confusing Lee a bit later in the piece with his father, William Lee (1739-1795), as his father had corresponded with Madison about emancipating his own enslaved persons. Mainly, I would back away from the link I made between the school and Black students. I think now that Lee had dealt with the question of education for those he had enslaved in the earlier paragraphs of his will which focused on his settlement of them in Baltimore and the education to be offered to those under eighteen. I think he then shifted his attention to the indigent students in James City County. That he did not specify them as being Black students suggests to me now that they were white. I’m still puzzled about siting the school where he did, at the site of the free Black community, but suppose now that the issue was centrality and accessibility to all students.

And I remain puzzled too about the teaching of American. I’m now inclined to think that the poorest of white children might just have spoken in slovenly ways to be corrected by instruction. Or perhaps, the reference to “American” was a means of signifying an approach or relationship to language that was distinctly American as opposed to British in the early years of the Republic.

Finally, Lee’s attention to democracy seems important here since it is unlikely he would have conceived of Blacks having a role in government. In his will—available at the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation’s Rockefeller Library—Lee writes that he is “convinced of the importance of education and of the advantages which may be derived from a general diffusal of useful information among the mass of society in Government depending for their support on popular opinion.” Few if any whites of the time conceived of African Americans ever having a role in governance.

What became of the school? It never came into being. As Earl Gregg Swem documented in his 1959 William & Mary Quarterly article, “The Lee Free School and the College of William and Mary,” the College did make some early efforts towards starting the school, but by 1837 the courts had deemed that William & Mary was not properly eligible to be a trustee of such a school. So the Williamsburg Bray School did have a daughter school—just not the one I thought it had.

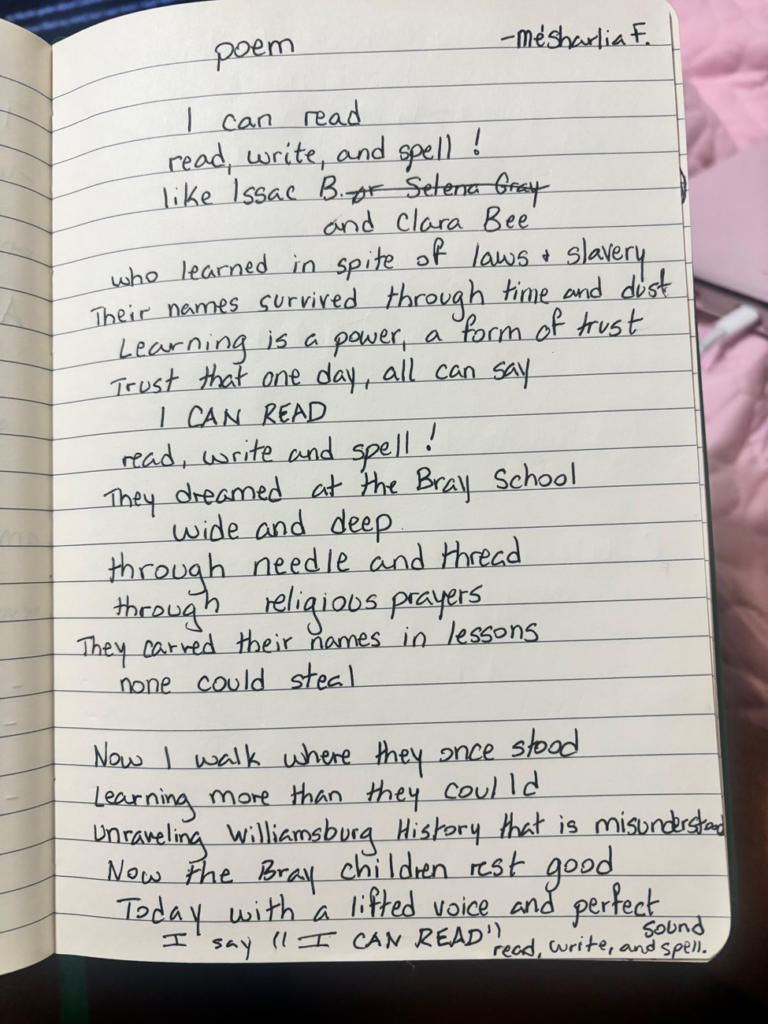

prior to its February 2023 relocation

to Colonial Williamsburg’s History Area.

Photo by Grace Helmick, W&M Strategic Cultural Partnerships

Terry L. Meyers, PhD, retired from William & Mary as Chancellor Professor, Emeritus, of English after 46 years of teaching. He was active with the Williamsburg Historical Records Association, which he served as president, and he was involved with the development of The Lemon Project at William & Mary. His research and unwavering curiosity about the Williamsburg Bray School were critical factors in the search that led to the ultimate rediscovery of the original tenement building in 2020. A family genealogist has recently suggested he is possibly descended from Leanna Nichols Spiller, a sister of long-serving Bray School Trustee, Robert Carter Nicholas.