It was dusk as I walked down Prince George Street, my partner and I enjoying a double scoop of Kilwins ice cream. As we passed the Bray-Digges House, the first home of the Williamsburg Bray School for enslaved and free Black children, we came across another couple standing in front of the building’s security fence. They were reading a sign concerning the research and archeological work being done under the partnership between William & Mary and The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation to research, relocate, and restore the Bray School. Thrilled, I rushed up to the pair and explained that I am a student volunteer involved in the project. It was simply the most exciting opportunity to discuss my experience and to express just how important the work being done by various volunteers, scholars, preservationists, and archeologists is to the understanding of our collective past.

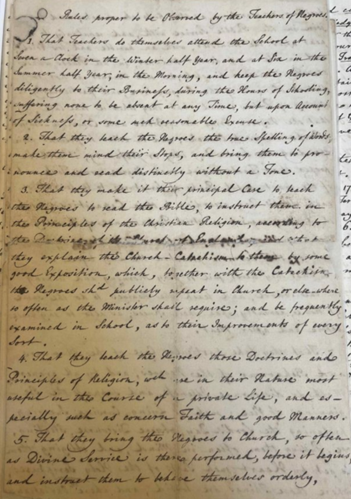

At the William & Mary Bray School Lab, I have been given the task of transcribing various primary documents, especially trustee letters and class lists, concerning the Bray Associates and the broader school system. Primarily I ensured that Transkribus, the AI software employed in reading documents, correctly captured and deciphered the authors’ handwriting and produced an accurate transcription. In the future, these transcriptions will be made available digitally to allow broad public access.

This transcription work is allowing us to study more closely the administrators and students involved with the Bray School. I have looked at and worked most closely with several documents concerning the rules of the Bray School, written by two early trustees, Reverend Thomas Dawson (ca. 1715-1760) and William Hunter (d. 1761). Thomas Dawson was the rector of Bruton Parish and president of the College of William & Mary; William Hunter was the colony’s official printer and publisher of the Virginia Gazette. These two men cemented the foundation for the Williamsburg Bray School and secured its opening on September 29, 1760. Ann Wager (ca. 1716–1774), the school’s sole teacher, was accountable for instructing the likely 300 to 400 children that came in her door between 1760 and 1774.

Courtesy of the USPG Bray Associates Collection, Weston Library, University of Oxford.

Photo by Nicole Brown.

Notably, the draft of school rules begins by ensuring that the students’ owners attend to keeping them “clean wash’d & combed.” This suggests that enslavers did not always keep Black children in a state of cleanliness. But the rule raises another question. Are Dawson and Hunter suggesting that cleanliness is not about hygiene, but rather a signifier of race or whiteness? If so, are they already drawing lines between the students and the whole of the white population by including such an assumption?

Dawson and Hunter continued, “Negroes be not condemned in their Faults, or their Teacher discouraged in the Performance of her Duty.” Seemingly more empathetic, Dawson and Hunter proposed that the students not be criticized for mistakes they may make in the classroom. By extension, Ann Wager should not be discouraged when efforts fail due to what they considered biological difference. Another rule expounds on this instruction with a list of behaviors to watch for: “they [Wager] take particular Care of the Manners and Behaviour of the Negroes, and by all proper / Methods discourage Idleness, and suppress the Beginnings of Vice; such as Lying, Cursing, Swearing, profaning the Lords-Day, obscene Discourse, Stealing.”

Together, the rules suggest that with proper adherence to “Religious Behaviour,” “both Master and Servant may be better inform’d of their Duty.” Through an appropriate understanding of the “Blessing of God,” as taught in their schools, Black children and white adults would be coworkers in maintaining and securing Virginia’s eighteenth-century slave society. They propose that Williamsburg’s “faulted” Black community may be more “civilized” and more useful when given a proper religious education. To be sure, many of the written rules naturally involve the students’ and the mistress’ religious commitment, but also include practical instructions such as what time school sessions should be held and Ann Wager’s salary (“£16 Sterling, or any sum not exceeding £20 Sterling. Per Ann”).

As a fourth-year Education student, I felt incredibly enlightened while reading these documents. I aspire to teach secondary education English Literature, and looking at these rules through the lens of my own experience, I feel a connection to fellow educator Ann Wager and to the students. I believe that I have taken away a critical knowledge of the eighteenth-century educational system and have also established a greater awareness of the systemic inequality and disparity that continues to weaken what is meant to be a central pillar of American democracy: public education for all. And, yes, while my exposure to these documents and correspondence has been at times disturbing, particularly as the language employed is fraught with racist terminology and meaning, recognizing these items is key in forming a progressive and inclusive American history–history I intend to share as a future educator. Indeed, I trust my work with the Bray School Lab will serve as illuminating material for generations to come.

Madeline Dort ’23

English

What truly resonates is the quality you admire in your mentor— a profound respect for the students’ intellect and potential. This respect is the cornerstone of effective teaching, fostering an environment where curiosity thrives. https://studyhelper.com/argumentative-essay-samples I’m eager to witness how you delve into this over the next two semesters, uncovering new layers of understanding and wisdom.