By Lee Cox

Gathering facts from 18th-century newspapers can be like putting together pieces of a puzzle — without the picture on the box. You are not entirely sure what you are looking for or if you even have all the pieces that you need. Every article yields clues, whether it is a runaway notice, a marriage announcement, or an estate dispute. These clues can be pieced together, providing a window into our nation’s history. Specifically, the legacy of Black Americans which is all too often forgotten, neglected, or ignored entirely. Initially, some articles may appear trivial, they can help us trace genealogies, inheritances, and provide insight into 18th-century social hierarchies.

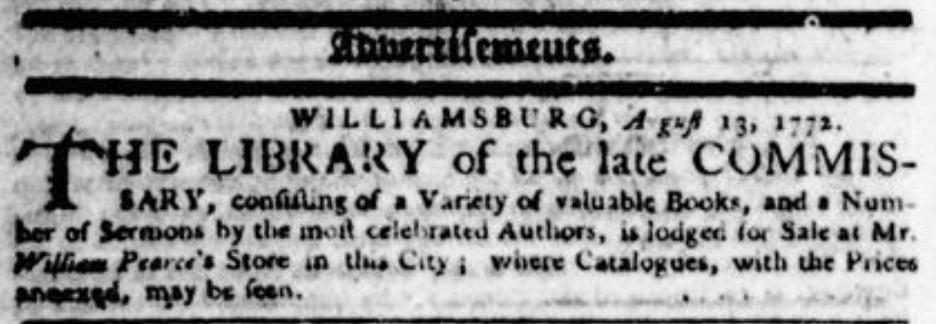

The Virginia Gazette was a vital source of information and communication in the colony, read by both commoners and members of the colonial elite. From legislative updates to personal notices of births, deaths, and marriages, the documentary source captures a historical snapshot of Williamsburg and the surrounding counties, one issue at a time. Each article I encountered, whether a small advertisement or a lengthy legal battle, offers hints regarding the intersections of family, property, and power.

The Virginia Gazette Project seeks to uncover information within colonial-era newspapers, pertaining to the families known to have sent children to the Williamsburg Bray School. Particularly, it seeks out information that sheds light on the lives and legacies of the individuals enslaved by these families.The scope of my research focuses on the Grymes family, a prominent household, who sent at least one enslaved child named Phillis to the Bray School in 1765.

Through my research, I have encountered references to at least three generations of the Grymes family. This family had a particularly complicated dynamic, as references often appear in the context of estate disputes. They reveal not just who stood to inherit land but also how each person was related, which properties were in question, and who might have owed money to whom. In the 18th century, a short announcement for the sale of an estate could signal major changes in the distribution of land and the movement of enslaved individuals. Reading these articles today allows us to reconstruct which family members were at odds, how wealth changed hands, and the financial consequences of family feuds. Due to the scarcity of records on enslaved individuals, we must use the enslavers as a proxy to uncover the lives of those whose own voices were rarely preserved.

Marriage also featured prominently, showing names like “Sukey” (Susannah) Grymes, who married Nathaniel Burwell. A notice of their union appeared in two editions of the Virginia Gazette on December 3, 1772 (one newspaper published by Alexander Purdie and John Dixon, the other by William Rind). This notice might seem little more than a social tidbit. Yet genealogically, that brief paragraph proves incredibly valuable. It confirms the link between two prominent families, both who had deep political and legal ties, and helps us understand how wealth and power were consolidated through familial alliances. These announcements proved useful as enslaved individuals were often subdivided across households when a new marriage was formed.

Estate sale announcements in the Virginia Gazette can also provide valuable information for genealogical research because they typically include a detailed accounting of property holdings. Because enslaved individuals were usually only recorded as property, such articles can provide records on the size of an enslaved community and the potential separation of families through sale. For example, a notice published on November 7, 1771, details the liquidation of a portion of the family estate by Benjamin Grymes. It details plans to sell approximately 120 enslaved individuals, to cover the estate’s debts. Those enslaved by the Grymes family would suffer the most due to the financial mismanagement of the estate. This sale marked the beginning of a lengthy family dispute, leading to a court injunction forcing Benjamin to relinquish control of the family’s estate. The details found in this series of notices will hopefully prove fruitful to ongoing genealogical research. Details such as the descriptions of specialized skill sets possessed by enslaved individuals, including, carters, forgemen, watermen, and a furnace keeper. Due to the lack of record keeping on the enslaved, these details regarding specialized skill sets can help researchers differentiate individuals that might otherwise be indistinguishable in the historical record. Also, details like the number of enslaved individuals sold and the dates of sale may prove useful when tracing the separation of families.

Among the grimmest documents found in the Gazette are the runaway advertisements, such as Phillip Ludwell’s notice from February 20, 1752, seeking Anthony, a young, enslaved man described as tall, slim, hollow-eyed, and marked by a burn scar on his wrist. These notices typically list the individual’s name, physical appearance, perceived manner of speaking or walking, and sometimes a significant scar or a specialized skillset. These descriptions are characterized by their despicable lack of dignity. From the enslaver’s perspective, these descriptions were intended to help readers recognize a “missing piece of property.” Yet for historians and descendants, each article is a testimony to a real person’s individuality, and the abhorrent reality of American slavery.

Behind every runaway advertisement in the Virginia Gazette stands the story of a real person willing to risk everything for the hope of freedom. These men, women, and children shouldered unimaginable danger, forging passes, braving harsh weather, and constantly eluding the patrols or those eager to claim a reward for their capture. Their quest was not just to escape physical bondage but to seize the most basic human rights: to choose their own paths, to live alongside their loved ones, and to determine their own futures. Though the notices often cast them as mere “property,” their acts of self-liberation shine with undeniable courage. The least we can do is restore a measure of their dignity by recognizing the extraordinary bravery and profound sacrifices they made in pursuit of their humanity.

Of course, this process takes time and is complicated by the lack of uniformity found in these 18th-century publications. References in these articles often vary in spelling, and locations may be referred to by multiple names. The name of an enslaved individual might be spelled differently from one article to another, or an enslaver might fail to mention a wife or child, creating confusion. While the Virginia Gazette rarely offers direct answers, it does provide building blocks for a broader picture. When we compile these articles and organize them by family, these newspaper clippings become a means of illuminating stories long obscured by conventional narratives.

Ultimately, the goal of this research is to rebuild lost connections. In dissecting these sources and assembling their clues, we affirm that every person’s name in the Virginia Gazette has a story worth telling. And while so many of those stories remain only partially recovered, the fragments we do find can guide us toward a deeper, more empathetic understanding of life in 18th-century Virginia. An understanding of our history that recognizes not just the colonial elite, but also the enslaved and marginalized individuals who quietly shaped the world around them.

Lee Cox is currently a Junior majoring in Economics and History and has served as a Student Thought Partner at the W&M Bray School Lab since the fall of 2024.