As a history major hoping to go into museums and preservation after school, I was excited to engage with the historic sites surrounding William & Mary’s campus. During my first semester, I found that the school does a phenomenal job of linking itself to local history. My first encounter with the Williamsburg Bray School was through a sociology course on twentieth-century Black Williamsburg, during which I was tasked with evaluating Colonial Williamsburg’s interpretations of various Black history sites. I found my tour of the Bray School fascinating, and was ecstatic when I was given the opportunity to become a student thought partner with the Bray School Lab.

I began interning at the Bray School Lab during the spring semester of my freshman year. At the time, I was a member of the Sharpe Community Scholars program’s Action Research Pathways, which connects students’ research interests with opportunities in the Williamsburg community. During their spring semester, Sharpe Scholars are placed into semester-long internships where they can put their research ideas and interests into action. Placement in each of the internship programs was interest-based, and my interest in the Bray School had already been piqued by my sociology course the semester before.

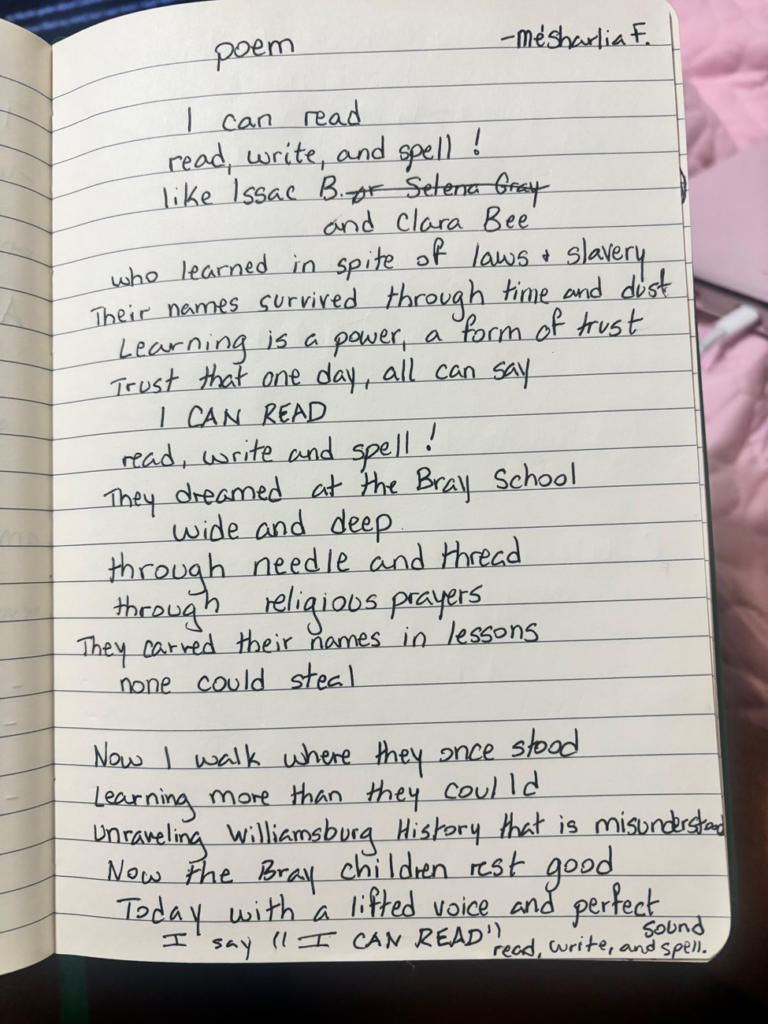

When I arrived at the Bray School Lab, I began working on the Mapping the Literacy of Enslaved Virginians project with a group of students, a few of which were also connected to the Lab through the Sharpe Scholars program. The project’s goal was to compile as much primary evidence of enslaved literacy in Virginia as possible, then map those instances onto an interactive map for the public to explore. I was struck by how many instances of enslaved literacy I found early on in my research — I had seriously underestimated how common it was.

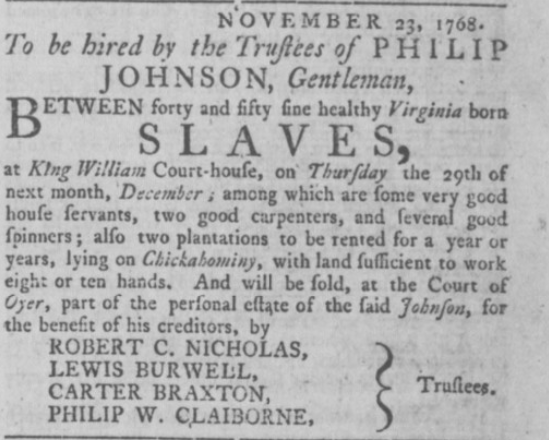

To find the names and literacy levels of many enslaved Virginians, I pored over fugitive slave ads, oral history transcripts, and teachers’ journals. Fugitive slave ads were one of my largest sources of information on enslaved literacy. They often included runaways’ education because enslavers were afraid of enslaved people reading the notices and making plans to go somewhere far away or forging freedom papers and passing as free. I scanned hundreds of ads in the Geography of Slavery in Virginia database for keywords like “read” and “write” and recorded the information in the Bray School Lab’s mapping project database.

In addition to reading and writing, I kept track of other forms of education and the skills enslaved Virginians had, such as printing or sewing. While the project focused on literacy, the Lab did not want to discount the many other important forms of education that enslaved Virginians possessed. I also kept track of enslaved Virginians’ sources of education. Some learned from their enslavers’ children as they learned to read in school, while others learned from night schools, reading the Bible, or friends and family members who were already literate.

In the process of reading through A North Side View of Slavery, edited by Benjamin Drew, one of the sources I used to get transcribed oral histories about enslaved literacy, I came across many remarkable stories. One man that Drew interviewed had learned to read and write and used these abilities to self-manumit by traveling from Virginia to Canada. By reading a message he’d been sent to deliver to another enslaver, he learned that his enslaver planned to sell him elsewhere. He escaped slavery by copying his enslaver’s signature and writing himself free passes until he made it to Queen’s Bush, Canada.

Enslaved literacy and education has often been overlooked in historical research, but the transcribed oral histories I read made it clear that these were crucial sources of power and agency for enslaved Virginians. There were many instances, like the one mentioned above, in which enslaved people were able to use information gained through their literacy to escape slavery, evade capture after running away, prevent themselves from being separated from their loved ones, or reunite themselves with family that had already been taken from them. That so many fugitive slave ads contained information about enslaved people’s literacy is a testament to how powerful that literacy was. Literacy was a symbol of freedom, and therefore a major threat to enslavers’ authority and methods of control.

Though I was only required to stay with the Bray School Lab for a semester as a Sharpe Scholar, the Mapping the Literacy of Enslaved Virginians project was much bigger in scope and historical significance than one semester of work. At the end of my freshman year, I made the decision to continue working with the Bray School Lab even after I left the Sharpe Scholars program. I am excited to help continue research for the project and see the final product. Hopefully, the mapping project will illustrate the significance of enslaved literacy and the nuances of enslaved Virginians’ experiences and expressions of agency.

Cadence Hodge ‘28 is a William & Mary sophomore double majoring in history and public health. She is also working towards a NIAHD certification in Public History and Material Culture. Cadence intends to pursue museum studies or public history in graduate school and hopes to be a part of making marginalized histories more accessible to the public.