by Tyler Lewis

Throughout Summer 2025, I had the opportunity to work as an intern for the W&M Bray School Lab with Genealogist Elizabeth Drembus, as part of the Office of Strategic Cultural Partnerships’ Cultural Heritage Immersion Program (CHIP). I engaged in genealogical research for three Bray School students: Squire of the Philip Johnson household as well as Hannah and Sarah of the Robert Carter Nicholas (RCN) household. These research endeavors were truly like a roller coaster that took the story of the scholars and their enslaved communities far beyond Williamsburg. Moreover, I recorded the names of every enslaved individual in the Johnson and Nicholas households to grasp a better understanding of their enslaved communities.

Squire and the Philip Johnson Household

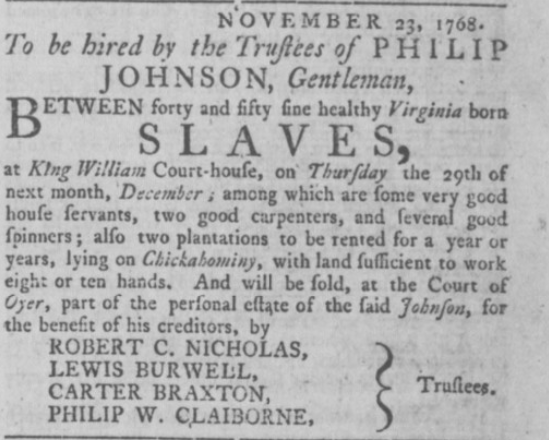

In 1765, Squire attended the Williamsburg Bray School, with Colonel Philip Johnson listed as his enslaver. Out of the three scholars that I researched, Squire had the most consistent paper trail. Legal documents and tax records placed him in the households of Philip Johnson and Sarah Johnson Lester (Johnson’s daughter) from the 1760s to 1792. While conducting this research, I wondered if there was something about Squire—either his skills, a connection to the Johnson family, or a high level of trust from the Johnsons—that made him seem worthy of receiving an education or remaining in the family. This is of particular note, since Philip Johnson was heavily in debt from the 1760s up to his death in 1789. Johnson and his trustees regularly advertised auctions and hiring out of enslaved people in the Virginia Gazette newspapers. We can only imagine how Squire felt while constantly facing separation from his relatives and other members of his enslaved community. Johnson shuffled or sold his enslaved people throughout numerous Tidewater and Piedmont counties. Squire’s Bray School instruction in reading and spelling would have enabled him to read about the annual divisions and sales taking place within his community.

Hannah, Sarah, and the Robert Carter Nicholas Household

In 1762, Hannah attended the Williamsburg Bray School as a student (aged around 7 years old) from the Robert Carter Nicholas household. Unfortunately, Hannah was the most elusive of the three scholars, as the only other definitive supporting document is Nicholas’ 1765 letter to Reverend John Waring of the Bray Associates in London. In the letter, Nicholas complained that despite Hannah attending the Bray School for three years, she turned out to be a “sad jade” amidst his attempts to reform her. I interpreted the letter as Hannah’s education transforming her from a passive recipient to one who courageously developed her sense of self. Meanwhile, Nicholas lamented that he lost control of Hannah and how she defied the school’s purpose (in Nicholas’ perspective) of indoctrinating Black children to embrace their fate in bondage.

In 1769, Sarah attended the Bray School as another student from the Robert Carter Nicholas household. Bruton Parish Baptism records describe Sarah’s family unit, with Lucy as her mother and Caesar as her younger brother. Sarah’s story also reveals many complexities regarding slavery, in terms of her tasks and who exactly enslaved her. By the 1780s, Sarah and her family labored on Nicholas’ Westham Plantation in Henrico County. However, Nicholas’ 1780 will contained a clause that divided all enslaved people at Westham who worked in the house between his sons Lewis and Philip, while his estate would continue to enslave those in the fields. Henrico tax records only list Nicholas’ estate without Sarah, yet she appears in court records discussing the enslaved people from Westham who were partitioned to Nicholas’ sons. This discrepancy leads me to believe that Sarah conducted domestic tasks while Lucy and Caesar cultivated cash crops.

Researching Hannah and Sarah taught me the importance of persistence in genealogical research. I had to document the enslaved communities and land speculation efforts for RCN’s children that stretched across various counties throughout Virginia, Kentucky, and New York. Frequent discussions of weavers in factories (in Albemarle, Virginia, and Geneva, New York) made me think of sewing and embroidery taught at the Bray School. Furthermore, various legal and personal papers for Nicholas’ children listed multiple enslaved women named Hannah or Sarah, which further complicated this research.

Reflection

I thoroughly enjoyed this summer internship because it perfectly encapsulated the Bray School Lab’s interdisciplinary nature in highlighting the students’ stories. It was also incredible to work within an extremely supportive environment alongside the Descendant Community, fellow CHIP co-workers, Bray School Lab supervisors, and other institutions. As an African-American man, it felt very gratifying to witness the passion of descendant communities in the Williamsburg area, Charlottesville, and throughout the country using genealogy to uplift our enslaved ancestors as heroes and agents in American history. In particular, engaging with the festivities on Descendants’ Day at James Monroe’s Highland revealed how institutional and descendant collaboration can highlight the importance of storytelling and humanize the experiences of the enslaved.

photo by Grace Helmick, W&M Strategic Cultural Partnerships

Tyler Lewis ‘26 is a William & Mary senior, studying history & anthropology. His previous genealogical experience includes researching enslaved communities for The Valentine Museum (Richmond, Virginia) and within his own family (with counties across Southside/Tidewater Virginia and the Carolinas). Tyler is continuing his research on Hannah, Sarah, and Squire this fall semester under the NIAHD Internship in Public History.