By Emily Wells

In 1762, a seven-year-old girl named Mary entered the Bray School in Williamsburg. The Associates of Dr. Bray hoped that this new institution would train Black students to be good Christians, obedient slaves, and skilled laborers. However, students could choose to apply their instruction in ways that did not fulfill the needs or prerogatives of their enslavers. Whether her time at the Bray School proved limiting or liberating, Mary returned each day to the home of her enslaver, Court Clerk Thomas Everard. There, she lived alongside his daughters, Frances and Martha Everard, who were also learning to take their place in society. The histories of Mary, Frances, and Martha are intertwined; rather than untangle the threads, it can be instructive to observe how and where they overlap.

As a student at the Bray School, Mary would have received instruction in reading, needlework, and “the Principles of the Christian Religion.” In the school’s regulations, the Associates expressed their hope that these subjects would help students become more useful and obedient to their enslavers. For example, they emphasized the importance of teaching students “Parts of the Holy Scripture” in which “Christians are commanded to be faithful & obedient to their Masters.” They encouraged enslavers to reinforce this message by “[catechizing] the Children at Home” and setting “good Examples of a sober & religious Behaviour.” Girls like Mary learned additional practical skills, such as “knitting sewing & such other Things as may be useful to their Owners.” Finally, the Associates hoped that all students would “instruct their Fellow Slaves at Home,” thus furthering the school’s mission.

At seven years old, Mary would have been old enough to learn the fundamentals of reading and needlework. Although it is unlikely that she learned to write, she may have stitched letters onto a sampler. A sampler produced by an eight-year-old girl at the Philadelphia Bray School in 1793 shows how this medium combined stitching and literacy.

Like Mary, Frances and Martha would have also learned to read and sew, likely producing samplers of their own. Unlike Mary, however, their instructors would have expected them to apply these skills, not as laborers, but as managers of domestic property. Although there are no documents that describe the particulars of their instruction, the sisters would have almost certainly cultivated the practical skills necessary to manage a household, including needlework, reading, writing, and arithmetic. They may have also studied subjects reserved for genteel young ladies including dancing and music. Frances and Martha likely took lessons at home under the direction of their mother or private tutors. They may have also taken lessons from local instructors, such as Mrs. Walker who in 1752 taught “young Ladies all Kinds of Needle Work.”

The genteel education that Frances and Martha received would have been of immediate use after their mother died in the late 1750s or early 1760s. After her death, the girls would have likely assisted their father in managing their household. As the elder sister, Frances would have taken on most of this responsibility, helping her father to manage the goods that circulated through the house and directing the labor of enslaved servants.

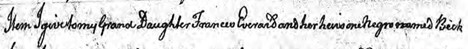

In 1762, the same year that Mary entered the Bray School, a teenaged Frances took on the role of enslaver as well as household manager. That year, Frances received a girl named Beck as a bequest from her maternal grandmother. When Frances married three years later, Beck likely travelled with her to her new home, forcing her to once again acclimate to a new environment. For Frances, this bequest represented a distribution of family wealth as well as a continuation of her education. While Mary was learning to be a better slave, Frances was learning to be an enslaver.

To better understand the significance of the Bray School, it is important to consider its place within the broader educational landscape of eighteenth-century Virginia. The educational norms and prerogatives that determined each girl’s instruction emanated from a common source: the desire to maintain and perpetuate the institution of slavery. However, girls also had the ability to push against these constraints when it suited them. Although Mary learned skills that would have made her more “useful” to her enslavers, her instruction would have also empowered her to provide for herself and her community. If Mary grew into adulthood, she could have used her needlework skills to provide herself with a small income and ensure that she and her loved ones remained clothed and warm. The relationships she formed with other students may have persevered into adulthood, providing her with additional community protection and support. While we do not know what became of Mary, it is important to consider these possibilities, to see where she might have plucked the thread of her own life from the pattern laid out before her.

Emily Wells is a graduate student in History at William & Mary. She began research on this topic as a Mellon Curatorial Intern at Colonial Williamsburg and would like to thank Kimberly Smith Ivey, Senior Curator of Textiles at Colonial Williamsburg, for her support and guidance.

For more on needlework in eighteenth-century Williamsburg, see Kimberly Smith Ivey, In the Neatest Manner: The Making of the Virginia Sampler Tradition (Curious Works Press and The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, 1997). For more on Mary D’Silver’s sampler, see Kelli Racine Coles, “Schoolgirl Embroideries & Black Girlhood in Antebellum Philadelphia,” Hidden Stories/Human Lives: Proceedings of the Textile Society of America 17th Biennial Symposium, October 15-17, 2020.